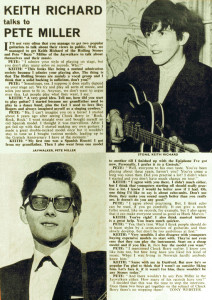

The amps themselves were born out of the experimentation of the 60s, where companies like JMI tried to respond to changing technology, and the desires / styles of the musicians of the time; the memories of Pete Miller (‘Big Boy Pete’) give us a good glimpse into this world. Touring alongside the Beatles in 1963 (and later alongside the Stones), he played in the Jaywalkers, who JMI would supply with gear and sometimes ask to try out their new products. They had a punishing schedule, and Pete tested the Vox gear to destruction, often finding it wanting. These extracts from his records though give us a real insight into the way touring bands like the Jaywalkers and the Beatles dealt with the various companies supplying them with gear. We also glimpse the sort of issues that were driving JMI/VOX to experiment with a new series of hybrid solid-state amps, the search for new, lighter, more rugged and reliable technology, and how they worked with bands to test and develop their products.

Regarding a trial of some Vox Guitars;

‘…Just after our endorsement deal with Vox, the Phantoms were introduced. One

afternoon we drove our bandwagon to the factory in Dartford and the good

people loaded it up with about a dozen AC30,s and about the same number of

Phantom guitars, including six stringers, twelve stringers, four string

basses and six string basses. These were early production models and

somewhat less than perfect. (We had been playing Fenders and Gretsches up

until that point). The amps were fine but the guitars were difficult to play

– doggy necks – shitty pick-ups and wanky tremolo systems which kept busting

strings.

In exasperation one night, on stage, I removed my Phantom, hurled it like a

javelin across the far side of the stage where it hit the wall and shattered

into a multitude of pieces which rained down all over our piano player.

Nonchalantly, I picked up Henry (my trusty Gretsch) and finished our set.

The audience loved it and thought it was part of the act. (This was quite a

few years before Townsend, Beck or Hendrix destroyed their instruments).

That night we happened to be on tour with Billy Fury et al, playing at

Slough Adelphi. Of course, Slough is close to Dartford in Kent. Unbeknown to

me, most of the Vox directors and top dudes were in the audience and bore

rude witness to the Phantom javelin-hurling incident.

In the intermission, our agent and manager stormed into our dressing room

and proceeded to verbally kick my arse and threaten my very being in the

group. I tried to explain that playing that Phantom was like trying to play

a ukelele with boxing gloves underwater.

But good things came to pass. A few weeks later, Vox presented us with a set

of Phantoms which were one-off specials. They bore Fender necks (carefully

disguised with the Vox headstock), and actual Fender pickups. They played

and sounded great.”

Big Boy Pete

Some biography extracts;

‘…Then came the stage full of Voxes. The band had two bass players and two guitar players and also needed a PA for the dance-hall tours. The endorsement deal with Vox was very generous. They would give us what we asked for whenever we asked for it and it arrived promptly. We didn’t take advantage and luckily this went on for a few years. Initially the Vox equipment was thrust upon us without us being able to select individual instruments, but it was free so nobody bitched. The AC30 amps were always great but after a while we became despondent with the poor sound quality and virtual unplayability of some of the Phantom guitar necks. The twelve-string guitar was just dreadful. The four-string bass wasn’t at all bad but the only instrument which really sounded great was the Phantom six-string bass. You can hear Pete soloing with this at the end of their “Poet and Peasant” record and also playing the introduction to “You Girl” on the Phantom 12-stringer.

Talking about endorsement deals, George Harrison also had one with Gretsch. I remember midway through the Beatles tour, we were playing Manchester I think, probably the Apollo theatre. The morning after the show we all arrived back at the theatre to pack up the gear and re-board the tour bus for the next night. Jack, our driver looked a little shocked and told us that the theatre had been broken into during the night and amongst other things, George’s Country Gentleman had been stolen. George, to my surprise was quite unfazed. “Doesn’t matter. Who cares. They’ll send me up another.” To me, the loss of your very own guitar is like losing a member of your family and in no uncertain terms I told him how I felt about his attitude. We had a bit of a barney about that. Anyway, when we arrived at the next town on the tour, a policeman was awaiting the bus with George’s Gent slung over his back. Looked kinda funny – with his Bobby’s helmet and all! He explained that the guitar had been found only a few blocks away from the Apollo theatre, just hanging on the wrought iron fence of a church graveyard. Maybe the thief had second thoughts.

…..

Another iconic date on that tour was November 22nd. We had played at The Globe theatre in Stockton that night and when we got back to the hotel, somebody switched on the TV in the bar. An announcer informed us that John Kennedy had just been murdered.

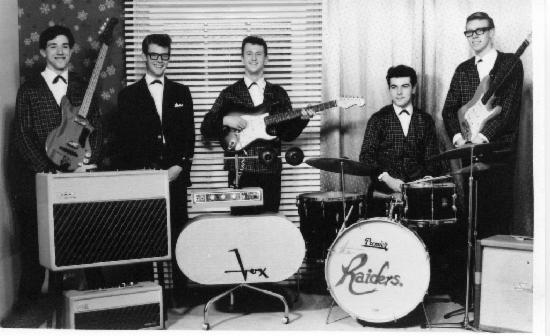

Soon after Vox started making solid-state amps, circa 1964, a pair of Vox Super Transonic amps were manufactured and given to the Jaywalkers to try out on stage. Pete believes they were the only pair ever to leave the factory. They were essentially fully-working prototypes which were given to the band to test on the road. After a quick trial we found they were unsuitable for public consumption and for any kind of bass or low-end instrument because of their small 3-inch tweeters. They were barely passable for lead guitar and rhythm guitar. We used them on tour for about a week before shipping the remains (I think in a coffin) back to the Vox factory in Dartford along with our disgruntled evaluation: In comparison to the trusty AC30s, they were a load of crap. The transistor amps sounded distorted, toneless, thin and nasty. The tweeters soon blew, the chrome hardware broke, the counter weights fell off, the casters broke, and the fuses continually blew. Even the Vox logo fell off. Needless to say, they never went into full production. The two 12-inch speakers in the lower cabinet were whatever Vox was using at that time in its AC 30s. However, the Super Transonic looked really cool. The amp and speaker cabinets were covered with the same orange vinyl cloth that was used later on the Vox Continental organ. The grill cloth was a light beige. The two tweeters were housed in circular chrome balls, balanced by a solid counterweight. They would rotate horizontally but not vertically”. *UPDATE; here are some pics we’ve found of another band using the rare super-transonic amps, Jamie & the Raiders, around 1963;

Soon after Vox started making solid-state amps, circa 1964, a pair of Vox Super Transonic amps were manufactured and given to the Jaywalkers to try out on stage. Pete believes they were the only pair ever to leave the factory. They were essentially fully-working prototypes which were given to the band to test on the road. After a quick trial we found they were unsuitable for public consumption and for any kind of bass or low-end instrument because of their small 3-inch tweeters. They were barely passable for lead guitar and rhythm guitar. We used them on tour for about a week before shipping the remains (I think in a coffin) back to the Vox factory in Dartford along with our disgruntled evaluation: In comparison to the trusty AC30s, they were a load of crap. The transistor amps sounded distorted, toneless, thin and nasty. The tweeters soon blew, the chrome hardware broke, the counter weights fell off, the casters broke, and the fuses continually blew. Even the Vox logo fell off. Needless to say, they never went into full production. The two 12-inch speakers in the lower cabinet were whatever Vox was using at that time in its AC 30s. However, the Super Transonic looked really cool. The amp and speaker cabinets were covered with the same orange vinyl cloth that was used later on the Vox Continental organ. The grill cloth was a light beige. The two tweeters were housed in circular chrome balls, balanced by a solid counterweight. They would rotate horizontally but not vertically”. *UPDATE; here are some pics we’ve found of another band using the rare super-transonic amps, Jamie & the Raiders, around 1963;

“…Vox had made a valiant but failed attempt to enter the cool. Like many other musical instrument manufacturers who over the ages have unsuccessfully tried to expand into new waters, it may have signaled the beginning of the end for the company. They panicked with more untoward and preposterous products such as the Electric Conga Drum which also has a story. It was essentially an oblong wooden black vinyl-covered wooden box with nothing but a microphone inside – and it had its own chrome stand. Of course it sported the Vox logo. My band The News took one of these to Thailand in 1969 (we were touring the US bases, working for the Vietnam GIs.) Firstly the “drum” got lost by Alitalia airlines and never arrived with the rest of our equipment in Bangkok.

Electric what? – (Jennings version)

A few weeks later Vox sent us a replacement and we used it for such sillyness as 50-minute jams on “In A Gadda Da Vida”, complete with Electric Conga Drum versus Electric Wah Wah Sitar solo battles. The drum acquired the name “The Electric What” because GI’s would come up to us on stage and ask “what’s that box we were beating on?” We’d tell them “It’s an electric Conga” and they would say “An electric what?”. “We also were privy to some of the very first Asian guitar and amp knock-offs. Most of them were quite dreadful and fairly obvious to any experienced picker that they came from cocoanut trees. They certainly wouldn’t get past George Gruhn – even at closing time. However, some GIs were fooled and bought them real cheap from the PXs. Many ended up back in the USA.

Vox also issued a small amount of ribbon microphones. Many of you may have noticed pictures of English Beat groups on stage singing through these oblong looking mics. They were actually manufactured by the Reslo company but Vox stuck their logo sticker onto the body of a few of them. They sound excellent with a warm delicate resonance. The only drawback is that ribbon mics are very fragile and don’t stand up to the rigorous road life very well. You can break the ribbon even by blowing into the mic. Our band would go through a couple of dozen of these every year. Pete still has one of these Vox/Reslos in his studio that he uses on occasion for special sounds. It works nicely miking a low-level Deluxe reverb, off-axis, from a distance of about twelve inches.

Upon hearing of our disappointment with the Phantom guitars as well as the Martian amps, Vox invited the whole band to come down to the factory one afternoon. “I remember getting excited seeing the Phantom guitar-organ on the workbench but it wasn’t quite ready for a test drive on that day. The people gave us cups of tea and a proud tour of their factory and we left with a van full of goodies, including about eight guitars and the same number of AC30s. They also supplied us with a hefty PA system which we would use on the dancehall circuit. This had a pair of Vox columns containing about six tens in each and a complementary mixer/amp of quantiful wattage. All this gear was quite enough for a couple of long arduous tours. We were working over 300 nights per year. It was on one of these tours that the javelin Phantom incident occurred. This resulted in a replacement one-of-a-kind pair of look-a-like Phantom guitars which to all intents and purposes, from a distance, looked just like the real thing, but actually contained Fender Strat pick-ups and fiendishly disguised Fender necks with the Phantom headstock glued on. Needless to say, they played and sounded great.

…

The AC30s not only suffered from overheating – even while working for short periods, but they’d start smoking and burst into flames every once in a while. We learned to use the stand-by switches at every available opportunity. Furthermore the cabinetry was less than stellar. Twelve months on the road being dumped daily into the cargo hold of the Timpsons tour bus by ex-wrestler Jack (our cigar-drenched driver) took a toll on the mortise-and-tenon joints which would gradually come apart due to the overheating. I remember picking mine up one day and the handle and top just popped away from the rest of the cabinet. Never mind – call Dartford.

I think even Paul would agree that the T60 was less than fulfilling for bass. (Dick) Denny would crucify me, bless his soul, but let’s be honest the AC30 was king. The rest was crap. Vox should have stuck with their valve amps and Jim Marshall might still be trading used gear in his Hanwell shop.

…

That night on stage at a dance hall gig in High Wycombe he (a Gretsch Anniversary) made his premier appearance. I remember being a little disappointed because his Hilotron pickups were not as strong as my Hofner Verithin’s although his tone was magnificent. A few months later George pointed it out to me after he’d used Henry on stage a couple of times: “Trade the Hilotrons for Filtertrons”. Yeah sure! Finding Gretsch parts in England? No way! (Both George and John would use Henry on stage occasionally – when their own instruments were out-of-commision due to broken strings etc. This was long before anybody had the luxury of roadie guitar-techs.)

..

While in London he heard of an Abbey Road tape-recorder that was looking for a new home. “It weighed about 400 lbs. We actually loaded the monster EMI machine into the trunk of my drummer’s Jaguar car (of course the door wouldn’t close) and drove it back to my home with the car riding at a 15 degree angle. The machine was far too heavy to get upstairs into my bedroom-studio so my mother kindly allowed me to move the studio downstairs into the lounge – which was sizable by English standards. We pulled a curtain across that corner of the room when guests were due to be entertained. It actually worked out well because Dad’s upright piano could now be implemented on my recordings. He wasn’t too keen on the thumb tacks I installed on the hammers. I told him to imagine he was playing a well tempered clavier!”

With Pete on lead guitar, the Jaywalkers enjoyed immense popularity in Britain, releasing a dozen singles for Decca and Pye records between 1961 and 1966. Many of these tracks were produced and engineered by the legendary Joe Meek (Outlaws, Tornados, Honeycombs, Heinz etc.) from Joe’s bedroom recording studio at 304 Holloway Road in London. It was from Joe that Pete learned many tricks of the trade as far as recording techniques are concerned which is quite apparent in the sounds on the Big Boy Pete records. It was around this time that Pete turned down an offer from Clem Cattini to join the Tornados – just days before they recorded the world-wide smash Telstar. No regrets!….”

Having toured with the Beatles and the Stones, Pete recorded one of the earliest classic psychedelic tracks (“Cold Turkey”), and later moved to the States, via Vietnam-War-time Laos (where he narrowly avoided becoming a guest of the Viet Cong).

There’s a fuller biography HERE, explaining how he went on to set up a studio in San Francisco, as well as a school for Audio engineers & producers. He has recently been working with his old friend Hilton Valentine (guitarist with the Animals).